Maritime cultural heritage

American Samoa contains maritime heritage resources representing more than 3,000 years of human history, and the sanctuary is legally responsible for helping protect and preserve those resources within its boundaries. Maritime heritage resources consist of cultural, archaeological, and historical properties associated with coastal and marine areas, and seafaring activities and traditions. In American Samoa, these resources reflect five different aspects of Samoan history: archaeological sites; marine and coastal natural resources associated with American Samoan legends, folklore, and culture; historic shipwrecks; World War II naval aircraft; and World War II fortifications, gun emplacements, and coastal pillboxes.

There has been no systematic field survey either by divers or by remote sensing methods directed at maritime heritage resources in American Samoa. Hence, much more remains to be learned about the wealth of prehistoric and historical maritime heritage resources here. Toward that end, the sanctuary’s 2012 management plan includes a cultural heritage and community engagement strategy outlining plans to inventory, assess, and protect maritime heritage resources within the sanctuary and broader American Samoa. Known resources are highlighted below.

Known historic resources within National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa

Fagatele Bay’s shores are the site of a historic coastal village occupied from prehistoric times through the 1950s. The bay contains one of the few marine archaeological records in the territory: grinding holes or bait cups, known as foaga, carved by ancient Samoans into the shoreline along the reef edge.

Fagalua Cove is the site of two turtle images carved in a boulder, as well as prehistoric fale (a traditional Samoan house) foundations. The cove may also contain buried archaeological deposits.

Ceramics and potsherds indicate that people were on Aunu`u Island as long as 2,000 years ago, although not much is known about the settlements at that time. This island is also the site of a whaling vessel lost at sea in 1835, and of ruins once used to hold the four cannons from Kaimiloa, a Hawaiian Kingdom steamer that was sent on an 1887 voyage in a display of power. The cannons were later used by the people of Aunu`u to repel a canoe fleet invasion and are now on display at the Jean B. Haydon Museum in Pago Pago. Other resources at Aunu`u include several sites associated with legends, buried archaeological deposits, wetland taro fields likely of prehistoric age, and the remains of an old light beacon.

Ta`u has 82 known historic properties island-wide, including prehistoric villages, star mounds (large, star-shaped raised platforms associated with the activities of higher ranking individuals), legend sites, wells, fish bait cups, petroglyphs, and buried archeological deposits. One particularly culturally significant site at Ta`u is that of Taisamasama, off the southern coast of the island within National Park of American Samoa (excluded from the sanctuary). Varying legends explain why the waters offshore from Taisamasama have a yellow hue, including that it results from a historical Kava ceremony between significant Samoan chiefs.

There are a number of maritime heritage resources at Rose Atoll within and outside sanctuary boundaries, including a Navy survey marker, a Naval Administration concrete monument from 1920 posting American Samoa’s claim to the atoll, an old fale foundation likely used by a family that briefly had a copra plantation on the island in the 19th century, and three known late 19th century shipwrecks.

Archaeological surveys have not been conducted at Swains Island, but it likely holds prehistoric sites and buried archeological artifacts. In addition, it may have some tupua (legendary sacred stones, rocks, or formations that represent ancient humans), and some buildings on the island may be historic.

Fautasi heritage

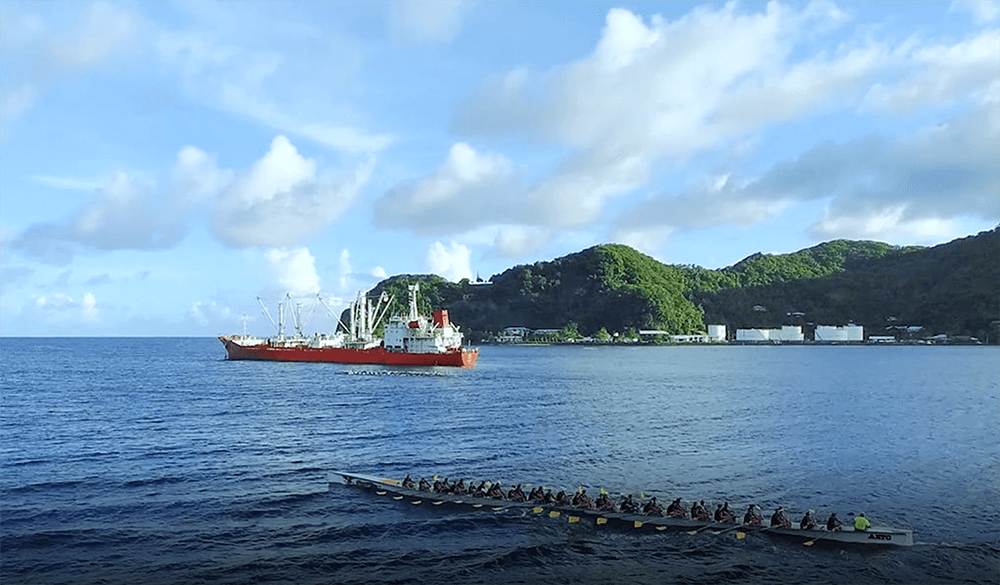

The fautasi longboat derives from the blending of Samoan watercraft and western whaleboat traditions, producing the paddled taumualua racing and war canoe by 1849. The refinement of the shorter tulula and subsequent fautasi (100ft+ Samoan longboats) followed in the 1890s. Intense desire for these unique vessels led to a notable building boom, often a unifying effort among each village. The adoption of oars and fixed rudders made these craft essential for all passenger/cargo service, racing competitions, and war parties between the islands. With the cessation of warfare and the incursion of powered vessels, the local roles for village fautasi slowly decreased over time to the one common remaining core: racing.

Today the sport of fautasi racing is the main event during Flag Day (April 17) celebrations in American Samoa. The entire village supports the training of their own team, which can span months prior to the race. Modern fautasi are adopting high tech lightweight competitive shells and carbon fiber oars, but the training, competitive spirit, and village pride remain true to the Samoan roots of fautasi heritage. Fautasi history, from warfare to racing, is part of the larger maritime cultural landscape of watercraft in Samoa.

Stories from the Blue: Fautasi

"To maintain our identity, that’s the most important thing to us."

National

Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa

National

Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa